How is it possible to maintain a sense of happiness and acceptance in the face of the ultimate challenge? For the last several weeks, SMC has taken a deep dive, case study-style, into the death experience of my mentor and friend, Jim Morris and his wife, Sue. In their diminishment and dying, they showed uncommon grace. We are exploring how their resilient dying flowed from their habits of resilient living.

You don’t have to be a realtor to know the three rules of home sales. Location. Location. Location. Similarly, you don’t have to be a psychologist to know three of the main ingredients for resilience. Relationships. Relationships. Relationships. By subtraction, the pandemic provided a grim illustration of that point. Take away our ability to connect with one another, and human beings get raggedy in every which way!

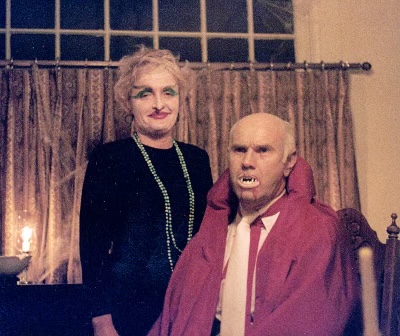

Over so many years, Jim Morris made substantial deposits into a vast array of relationships. Those investments paid out untold dividends of happiness and resilience for him. The successful Catholic retreat program, Koinonia, that he and his wife authored and championed nationally and internationally resulted in over 50,000 lives changed for the better. Who knows how many friendships were born out of that program for Jim and his wife Sue? The flow of drop-in guests at their home at all times of the day and night was constant. I should know, I was one of them. It was rare that I was the only one dropping in. At the time, it was unclear to me if their front door had been fitted with a lock? Occasionally a guest would outstay their welcome, but overall, this decades-long ministry of spontaneous hospitality appeared to energize this extroverted couple.

Years of diminishment, leading to assisted living, substantially culled Jim’s universe of relationships. The smallish group that stuck with him included his men’s prayer group that met on a monthly basis at the nursing home, as well as a few other devoted friends. Perhaps his wisest relationship investments, that continued to pay out till the very end, were his children—particularly his in-town daughter, Sarah, and her family. Along with her husband, Nick, their four children, and the five other Morris siblings… these were the invisible hands that buoyed up both Jim, as well as his Parkinson’s riddled wife, Sue, for their final years.

Observing the interactions between senescent Jim and his children, there was something more here than mere “duty”driving their support of him. What was that “something more?” As I see it, when the care-giving shoe was on the other foot, Jim and Sue consistently provided empathetic care, friendship, and enrichment for their children. That “something more than duty” that shows up in adult children has been studied in family system’s research (Ivan Bozormeni-Nagy, 1973, Invisible Loyalties). It has been described as a kind of fundamental unconscious gratitude that builds in people who experiencelong-term investments of ongoing faithful love given to them. Those investments have a way of appreciating into a kind of unconscious and fundamental motivation to give to others. Another way to say this in a nutshell, if ”hurt-people, hurt people,” then the opposite is at least as true. Well-loved people tend to look for ways to love others. In his final years and days, Jim’s adult children possessed an instinct to give back to him, and in the giving back, created a store of gratitude and equanimity in their father that stayed with him all the way till the end.

Remembrance

There is a theology of remembrance in many Christian denominations that was coopted from the Jewish tradition. In the sacred telling, and the enactment of the sacred rituals, The Passover is not so much thought of as an event that is being viewed like nostalgic or heroic scenes from a dusty past. In the telling and the doing, it’s more like those events become present for the participants in the current time zone connecting them to the Transcendent, shaping identity, as well as forming community. Christians see their Eucharistic narrative and ritual in a similar way. The participants aren’t caught in a past event, they’re more caught up in a current reality that’s unfolding here-and-now, shaping their lives at a very deep level.

I’ve come to understand the late stage care-giving of Jim and Sue’s adult children that way. In his diminishing and dying, I watched them creatively “remember him” back into the present. This is a subtle, but important point. By way of illustration, in an earlier SMC post (Oct 1), I shared that Jim once told me that he could remember and sing the lyrics and melodies of over 800 songs. I had no reason to doubt it. In my last several visits before he died, with his memory impaired, I had to remember that version of Jim into the present. As I sang with him, the guy who led so many singalong flash mobs, was studying my face, and listening for the words of songs he had taught me. A word off my lips would download another lyric that he would then sing along with me. I went slowly, and emphasized the next prompt, and then we would sing some more lyrics. In this way, an essential aspect of Jim, covered over by his stroke-damaged brain could re-enter the world momentarily.

I regularly observe this dynamic at my mom’s memory care facility. On Thanksgiving weekend, my daughter played some old favorites on her violin while the residents sang along. Way over in the corner, I saw Mrs. Callahan, the stunningly beautiful mother of my equally beautiful high school classmate, Theresa. Alzheimer’s Disease had practically cemented her into her wheelchair. Her adult son remembered for her that she used to love ballroom dancing. With strong arms and a strong sense of his mother, he remembered a fundamental part of her back into this time zone. In his re-collecting her, he momentarily gave her back her girl graces as a down-payment on a future cleansed of amyloid proteins, wheel chairs, and a brain that could no longer keep up with her beautiful soul.

Conclusion

There is a myth in America of the self-made person. By strength of will, physique, or self-actualization, the story goes, “you can do anything!” Mountains of psychological research have put the lie to that myth. No one accomplishes anything without the unseen hands of a community buoying them up. I have asserted for many years that resilience can be likened to a muscle that can be grown through practice. But the truth about muscles is that they require the intricate ecosystem of a body rich in nutrients for proper functioning. That ecosystem for all of us is the community in which we are embedded that either supports or impedes the exercise of our flourishing.

Questions for Conversation

• How do you make space for relationships in your life?

• Who knows you at least as well as you know yourself?

• Who draws the best out of you?

• For whom do you practice the art of remembering? Do you think this is necessary even for people without dementia?

• Whose investments in you changed your life for the better? Tell that story.

• Whose life have you changed for the better? Tell that story.