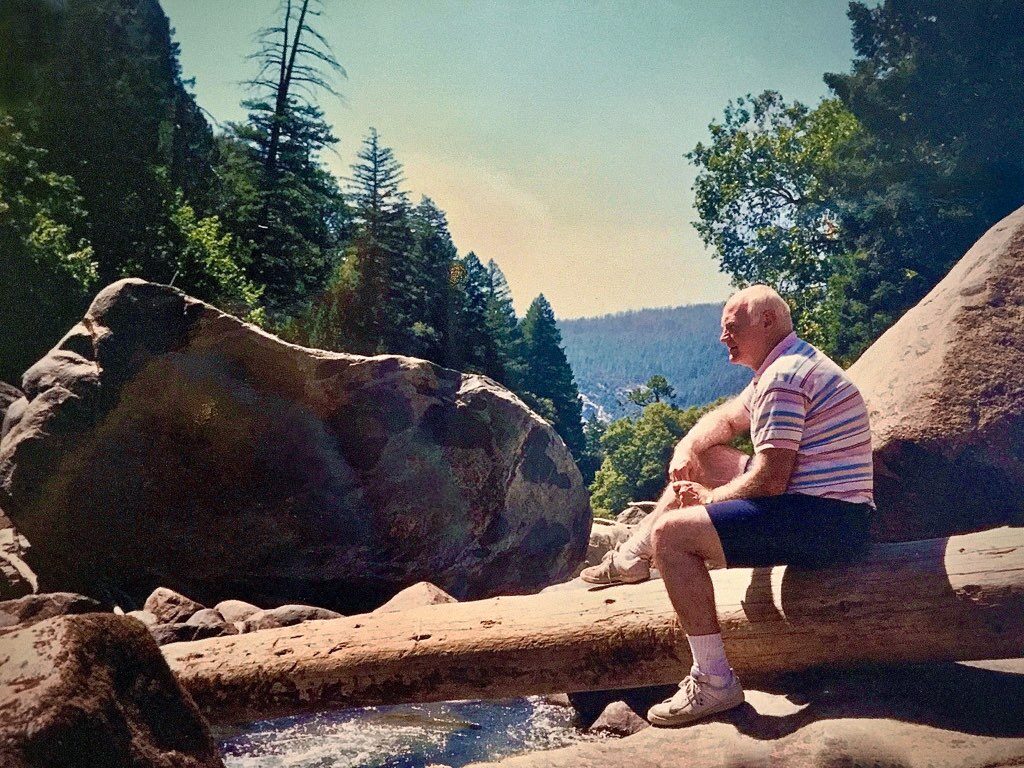

I want to return to a story from last week that took place years ago, just outside a Surgical Suite. I hope to do a little psychological surgery of my own to examine the active ingredients involved in the kinds of profound changes that lead to flourishing. This represents the sixth in a series of articles that researches the uncommon resilience of my mentor from adolescence, Jim Morris. As you may recall from last week, it was in the Neurosurgery Waiting Room where Jim got the news that his wife’s brain implant to reduce the symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease, was freshly in place… BUT… (caps intended) … her brain may have been injured due to a brief lack of oxygen. I was there to hear Jim’s first words after the taciturn brain-plumber fled the room: “Interesting that my first thought was, ‘How will this impact my life?’ ” Jim was acknowledging that his initial consideration was more about himself than his wife, more ego than other-centered. For those of you who read last week’s article, you know that I believe that this was one of those moments that divides the “before” from the “after.” It marked a radical turning where Jim became a Grade A, Blue Ribbon, Gold Medal, Counter-Cultural, Full-Service Husband. Which leads me to reflect back on what I believe to be the source of Jim’s surgical-waiting-room realization. Observing him over the years, I am convinced, that the condition for the possibility of this transformationwas Jim’s contemplative practice.

I don’t know if his time in meditation ever eclipsed the hours he spent watching his beloved St. Louis Cardinal’s baseball, or Notre Dame football? I can say with certitude that his daily sitting in contemplation far outstripped my own practice of two twenty-minute sessions a day. Somewhere in the 1980’s, the author and speaker, Anthony DeMello, SJ, introduced him to some contemplative recipes that Jim folded into his life. Many years later, in his second-to-last assisted living residence, I would come to visit, and regularly find him in the chapel, hands empty, eyes closed, sitting up straight, frequently, but not always smiling.

Anyone devoted to a meditative practice from any religious tradition (or secular for that matter), will eventually stumble upon the same phenomena. First, they will notice the endless stream of automatic thoughts and feelings, as well as the boxes and bags filled with postcards and short movie-clips from the imagination. If you’re able to nurture a non-judgmental curiosity, a recognition of patterns can emerge from this babbling river of content. Mindfulness experts like Tara Brach encourage a mental holding of these experiences at an objective distance. She calls it, “non-identification.” This practice results in awareness’s like, “I am more than this thought.” “I am having this feeling, but I am not this feeling.” This creates a soothed down heart that paradoxically, can help you own the previously split-off-from-consciousness parts of the self.

I am virtually certain that, by the time of his experience in the neuro-surgery waiting room, Jim had reached this point of maturation in his spiritual journey. His hours and hours in contemplation allowed him to notice his own ego at work in real time. A more secular or Buddhist practice of mindfulness would have the practitioner strive for deep compassion for the self when contacting what Carl Jung called, “The Shadow.” The Christian contemplative, approaches their practice similarly, but in just a slightly different way. They hope to bask in a Personal, all-encompassing Love that is infatuated with the one doing the contemplating. They strive to simply do what Psalm 131 says to do:

“Oh God, my heart is not proud,

Nor do my eyes strive for things far beyond me.

In the silence, I have stilled my soul,

Like a weaned child at rest on its mother’s lap.”

This would be seen as the necessary foundation for real change by Christian spiritual masters like Mechthild of Magdeburg, Theresa of Avila, or Ignatius Loyola, among others. According to the mystics, the light to see the “false self” (Karen Horney, 1950, “Neurosis and Human Health”) hiding in the dark, is the experience of full acceptance and love by God, especially in one’s darkest places. In other words, it takes “Amazing Grace” to find the courage to accept the “wretch like me” part of things. For a contemplative, this two-step process is the mechanism that leads to deep and lasting change.

I believe that what allowed Jim to notice his own shadow in that waiting room was the fruit of his contemplative practice. It gave him both the ability to notice his Shadow at work, as well as a deep sense of self-compassion born of hours resting in an All Embracing, All Accepting Love. It’s that foundation that softens the ego’s need to justify, feel sorry for one’s self, and dodge the call to become more Loving, more Truthful, more Good, and more Beautiful. It was this root system that produced the fruit and flower of what Jim said “was the best years of [his] marriage.”

Questions for Conversation

- When have you felt known and loved even in your darkest places?

- Share a time when you had a spiritual experience.

- What are the usual practices you do to encounter God’s warm embrace, or depending upon your spirituality, to encounter a deeper sense of Beauty, or Harmony, or Acceptance?

- Where could you insert more of a contemplative practice into your days (even for a few minutes)?

- With whom do you discuss the deep down things?